It's time for our third annual Halloween tribute post! But in keeping with the zeitgeist, USA Today reports that this year's celebrations might be a little muted: "The frightful economy is scaring many people into a thriftier, more homemade Halloween." Time doesn't lighten this mood much, asking "Is Trick-or-Treating Dangerous?" And in the Guardian, Tim Dowling berates the UK for its attitude to the holiday: "You have taken the tradition and given it your own twist, adding an element of threat and a general air of resentment at being coerced into participating." Fair enough. So why not ignore the hoopla and curl up with a good book this Halloween? And why not go back to basics? Below, you can enjoy "The Haunted House" from Washington Irving's Bracebridge Hall (1822).

It's time for our third annual Halloween tribute post! But in keeping with the zeitgeist, USA Today reports that this year's celebrations might be a little muted: "The frightful economy is scaring many people into a thriftier, more homemade Halloween." Time doesn't lighten this mood much, asking "Is Trick-or-Treating Dangerous?" And in the Guardian, Tim Dowling berates the UK for its attitude to the holiday: "You have taken the tradition and given it your own twist, adding an element of threat and a general air of resentment at being coerced into participating." Fair enough. So why not ignore the hoopla and curl up with a good book this Halloween? And why not go back to basics? Below, you can enjoy "The Haunted House" from Washington Irving's Bracebridge Hall (1822).Friday 30 October 2009

News: Happy Halloween

It's time for our third annual Halloween tribute post! But in keeping with the zeitgeist, USA Today reports that this year's celebrations might be a little muted: "The frightful economy is scaring many people into a thriftier, more homemade Halloween." Time doesn't lighten this mood much, asking "Is Trick-or-Treating Dangerous?" And in the Guardian, Tim Dowling berates the UK for its attitude to the holiday: "You have taken the tradition and given it your own twist, adding an element of threat and a general air of resentment at being coerced into participating." Fair enough. So why not ignore the hoopla and curl up with a good book this Halloween? And why not go back to basics? Below, you can enjoy "The Haunted House" from Washington Irving's Bracebridge Hall (1822).

It's time for our third annual Halloween tribute post! But in keeping with the zeitgeist, USA Today reports that this year's celebrations might be a little muted: "The frightful economy is scaring many people into a thriftier, more homemade Halloween." Time doesn't lighten this mood much, asking "Is Trick-or-Treating Dangerous?" And in the Guardian, Tim Dowling berates the UK for its attitude to the holiday: "You have taken the tradition and given it your own twist, adding an element of threat and a general air of resentment at being coerced into participating." Fair enough. So why not ignore the hoopla and curl up with a good book this Halloween? And why not go back to basics? Below, you can enjoy "The Haunted House" from Washington Irving's Bracebridge Hall (1822).Monday 19 October 2009

Research Seminar: Kevin Annett

A change from the norm: this week's research seminar will be a film screening and discussion of Kevin Annett's documentary about the North American residential school system, Unrepentant. Trailer below.

A change from the norm: this week's research seminar will be a film screening and discussion of Kevin Annett's documentary about the North American residential school system, Unrepentant. Trailer below.Please note time and location: Wednesday 21st October, Lecture Theatre 4, 4pm. All welcome.

Friday 16 October 2009

News: Race-Mixing, Mixed-Up Judge

We've all been enjoying the TV show Flashforward recently, but how about this for a flashback? A Louisiana Justice of the Peace has refused a man and a woman a marriage license on the grounds that they are a mixed race couple. But all for their own good, he says. Yes, he refused to issue a marriage licence to the interracial couple out of concern for any children the couple might have. Keith Bardwell, justice of the peace in Tangipahoa parish, said it was his experience that most interracial marriages did not last long. You’ll be glad to hear, though, that he’s not prejudiced: "I'm not a racist. I just don't believe in mixing the races that way," Bardwell said. "I have piles and piles of black friends. They come to my home, I marry them, they use my bathroom. I treat them just like everyone else." Coverage on this can be found in the Guardian, Salon, The Week and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

We've all been enjoying the TV show Flashforward recently, but how about this for a flashback? A Louisiana Justice of the Peace has refused a man and a woman a marriage license on the grounds that they are a mixed race couple. But all for their own good, he says. Yes, he refused to issue a marriage licence to the interracial couple out of concern for any children the couple might have. Keith Bardwell, justice of the peace in Tangipahoa parish, said it was his experience that most interracial marriages did not last long. You’ll be glad to hear, though, that he’s not prejudiced: "I'm not a racist. I just don't believe in mixing the races that way," Bardwell said. "I have piles and piles of black friends. They come to my home, I marry them, they use my bathroom. I treat them just like everyone else." Coverage on this can be found in the Guardian, Salon, The Week and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Wednesday 14 October 2009

Invitation: Private Screening & Discussion

A date for your diaries: on Wednesday 11th November (in Lecture Theatre 4), everyone is invited to a private screening and discussion of A Regular Black: The Hidden Wuthering Heights, a 25-minute film examining the racial construction of Heathcliff.

A date for your diaries: on Wednesday 11th November (in Lecture Theatre 4), everyone is invited to a private screening and discussion of A Regular Black: The Hidden Wuthering Heights, a 25-minute film examining the racial construction of Heathcliff.The film is the creation of BBC Arena director Adam Low and producer Martin Rosenbaum, whose recent films for Arena include the The Strange Luck of V.S. Naipaul, The Hunt for Moby-Dick, T.S. Eliot and Calling Hedy Lamarr. Other films include The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema with Slavoj Zizek, described as “a virtuoso marriage of image and thought” by Variety and “an extraordinary reassessment of cinema” by The Times. For further information on LoneStar Productions you can visit their website, here.

Tuesday 13 October 2009

Research Seminar: Alison Stanley

At this week's research seminar, Alison Stanley (King's College London) will be talking about: "'The Reformation of their disordered lives': Portraying cultural adaptation in the 17th century Praying Indian towns."

At this week's research seminar, Alison Stanley (King's College London) will be talking about: "'The Reformation of their disordered lives': Portraying cultural adaptation in the 17th century Praying Indian towns."Wednesday 14th October, A2.51, 4pm. All welcome.

Monday 12 October 2009

News: Ira Aldridge

For Radio 4, Kwame Kwei-Armah explores the life and career of Ira Aldridge, the New York born actor who managed to carve a place for himself on the nineteenth century stage. You can also read a good snippet of Bernth Lindfor's biography of Aldridge on Google Books:

For Radio 4, Kwame Kwei-Armah explores the life and career of Ira Aldridge, the New York born actor who managed to carve a place for himself on the nineteenth century stage. You can also read a good snippet of Bernth Lindfor's biography of Aldridge on Google Books:

Friday 9 October 2009

News: Barack Obama Wins Nobel Peace Prize

Barack Obama might have lost the olympics, but he has won the Nobel Peace Prize for 'extraordinary efforts' to improve world diplomacy and co-operation

Barack Obama might have lost the olympics, but he has won the Nobel Peace Prize for 'extraordinary efforts' to improve world diplomacy and co-operationObama joins former Presidents Jimmy Carter (2002), Woodrow Wilson (1919) and Teddy Roosevelt (1906) in winning the prize. He is the third president to receive the award while in office, after Wilson and Roosevelt.

Jimmy Carter received the prize seven years ago for his international human rights work. Check out the Carter Center website.

Wilson won his prize for founding the League of Nations - although, ironically, the USA would not become a member of the organization. In 1919 Wilson became embroiled in a grueling battle with the US Senate over the issue and, while on a punishing tour of the nation to promote the League, he suffered a physical collapse and a debilitating stroke that left him partially paralyzed. A steely Senate nevertheless voted against membership in November.

Roosevelt’s part in drawing up the peace treaty that ended war between Japan and Russia in 1905 won him his prize. As everyone knows, the teddy bear is named after Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, but he was not a particularly cuddly character. He liked to project a tough, outdoorsy sort of image, and his Presidency is best known for his crusade against big business in the name of “progressive” liberalism. He is remembered today for his foreign policy aphorism “speak softly and carry a big stick” and he made a show of American military strength on the world stage at a time when the nation was emerging as a major power. Latterly, in 1912, Roosevelt became the combative Presidential candidate for the Progressive Party in his second run for the White House: he finished second behind future fellow Nobel laureate Woodrow Wilson.

Thursday 8 October 2009

News: Black Music?

From The Root, a discussion about the significance of the term "black music". First up, Greg Tate argues that it's still a valid and necessary term:

From The Root, a discussion about the significance of the term "black music". First up, Greg Tate argues that it's still a valid and necessary term:While I like parsing race semantics as much as the next philologist (not to be confused with a cat who studies all things outta Philly) at a certain point, one has to just know when you've entered the realm of the naively unscientific, the demonstrably ahistorical and the patently absurd. Dispensing with the rubric, black music is clearly such an endeavor where we'd risk not only losing our soul but our rhetorical edge and swagger and in the name of whut, Negro, whut? Some lame, nebulous and namby-pamby post-racialism, that's what.And on the flip side, Cord Jefferson makes the case against:

Basketball was invented by a white physical education teacher for his white students. But no one would ever think to call basketball a "white sport;" to speak in those terms about something that's changed so much over the years would be silly. Similarly, Spike Lee has said that he takes directional cues from Italian-American Martin Scorsese, and Akira Kurosawa, the Japanese director of Seven Samurai, but would anyone say Do the Right Thing is a Japanese film? Of course not. Yet music critics, fans and historians don't think twice about calling the music of Aesop Rock, Eminem or the Mountain Brothers, an acclaimed Asian-American hip-hop group from Philadelphia, "black music."So what do you think? Do you like black music?

Wednesday 7 October 2009

News: White House Art

Above, George Catlin's Catlin and Indian Attacking Buffalo (1861/1869) - which has just become one of the images that the Obamas have introduced to the White House. As The Times reports:

Above, George Catlin's Catlin and Indian Attacking Buffalo (1861/1869) - which has just become one of the images that the Obamas have introduced to the White House. As The Times reports:A cultural revolution is under way at the White House, where the Obamas are decorating their living quarters with modern and abstract artwork. Out have gone traditional landscapes, portraits and still life paintings. In have come new pieces by contemporary African-American and Native American artists, with bold colours, odd shapes and squiggly lines.More on these artistic changes in The New York Times and First Things.

Tuesday 6 October 2009

News: What makes Gatsby great?

That's a question that AMS's very own Sarah Churchwell has been answering for The Times.

That's a question that AMS's very own Sarah Churchwell has been answering for The Times.Here's an excerpt:

Gatsby is a connoisseur's guide to the glamour and glitter of the Jazz Age, but it's also a nearly prophetic glimpse into the world to come. Writing at the height of the boom, in the midst of the Roaring Twenties, Fitzgerald detected the ephemerality, fakery and corruption always lurking at the heart of the great American success story. Four years later, the market would crash - but the age of advertisement that Fitzgerald was among the first to condemn had only just begun. Nearly a century later, his cautionary tale has become all too apt once more, anticipating our own boom and bust, our tarnished dreams and tawdry failures.The whole article is available here.

Monday 5 October 2009

Research Seminar: Linda Freedman

At the first Research Seminar of the year, Dr Linda Freedman (Selwyn College, University of Cambridge) will be talking about: "Blake, Whitman and Crane: The Prophet-Artist and Democratic Thought.

At the first Research Seminar of the year, Dr Linda Freedman (Selwyn College, University of Cambridge) will be talking about: "Blake, Whitman and Crane: The Prophet-Artist and Democratic Thought.Wednesday 7th October, 4pm, A2.51. All welcome.

Friday 2 October 2009

News: Late Writing

Coming soon: a host of new works by dead writers, nearly all of them vital figures in the development of American literature - Vladimir Nabokov, William Styron, Kurt Vonnegut, Ralph Ellison and David Foster Wallace. Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Alexandra Alter examines this new trend. She also speaks to the venerable Robert Hirst, general editor of the Mark Twain Papers, who defends the publication of such fragmentary, unfinished or fugitive works:

Coming soon: a host of new works by dead writers, nearly all of them vital figures in the development of American literature - Vladimir Nabokov, William Styron, Kurt Vonnegut, Ralph Ellison and David Foster Wallace. Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Alexandra Alter examines this new trend. She also speaks to the venerable Robert Hirst, general editor of the Mark Twain Papers, who defends the publication of such fragmentary, unfinished or fugitive works:"You can learn a lot about how he thought and wrote that you can't learn from reading an edition of Huckleberry Finn," Mr. Hirst said. "I don't think anything we publish can damage his reputation."So are you looking forward to the emergence of these texts? Or should they stay in the archives?

Thursday 1 October 2009

Guest Post: Alex Jenkins

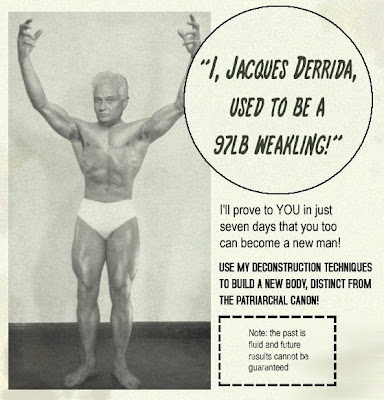

With regard to scholarly writing, authors generally fall into two camps: those who insist on the importance of articulating one’s ideas as clearly as possible, and those who claim that complex ideas demand a similarly complex prose style. Both camps are, to an extent, correct. Jacques Derrida’s Limited Inc demonstrates the tension between John Searle’s maxim “if you can’t say it clearly you don’t understand it yourself”, and Derrida’s commitment to linguistic uncertainty, an uncertainty he delights in incorporating into his prose. Critiquing the axioms underpinning language and questioning what it is to “mean” something is a tricky business, and is often necessarily abstruse; moreover, the rigorous critique of assumed critical axioms can be a profitable enterprise.

Nevertheless, this piece contends that scholarly writing is sometimes over-reliant on deconstruction, and this affects both the quality of prose and the quality of critical thinking. (Its title is a reference to George Orwell’s infamous translation of a passage from Ecclesiastes, which transforms the poetry of the original into stultifying abstractions.) An example: I have in front of me a book chapter, by Robert Stam, entitled “Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation.” As a piece of writing, and as a piece of critical thinking, it is both persuasive (if overwrought) and unintentionally silly.

It is relatively easy to demonstrate the former claim. The chapter begins with a sensible, if pedestrian, discussion of the problems of fidelity in film adaptations, and makes the inarguable, if obvious, claim that the mechanics of film-making are necessarily different to the mechanics of novel-writing. There follows a summary of the tenets of deconstructionism, which for a novitiate to cultural or literary theory is confusing but is at least short. Where “Dialogics” really hits its laboured stride, however, is when its author proudly coins the phrase ‘diacritical specificity (59).’ (And the author really is proud of his creation: he calls it ‘A more satisfying formulation….’) This jargon is inexcusable for two reasons: firstly, it’s mentally horrifically taxing to parse; and secondly, the subsequent explanation of the term does little to elucidate it. To cut some prolix short, Stam’s coinage refers to film’s ability to marshal numerous visual and auditory resources, whereas a novel must stick to words.

Things get worse. In particular, one sentence ends with the pleonastic clause, ‘thus insinuating a deeper subterranean unity linking these apparently antagonistic characters (61).’ Deeper subterranean? As in sub-subterranean? How far below the Earth’s crust are we talking here? And I know that it’s stylistically clunky to use the same word repeatedly in a short space, but I am more than willing to grant an exception to Stam; to use anthropophagic to avoid repeating the word cannibalism tempts me to take the “death of the author” concept more literally than Barthes intended. I am not against complex, polysyllabic words, nor do I mind jargon, providing it’s not wincingly self-aggrandising. Often, one long word either saves writing several, or it offers precision of meaning that the latter cannot.

And so, as a proleptic response to potential “he who is without sin” type arguments, I will admit to being seduced by critical jargon. I once argued that, with reference to Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, post-structuralist critical theory offered an opportunity for a culturally nourishing “ludic Luddism.” In my defence, however, I was gunning for assonance. Now witness the following sentence: ‘in the cinema the performer also brings along a kind of baggage, a thespian intertext formed by the totality of antecedent roles (60).’ Translation: actors have been in other movies; people watching a film will therefore remember their previous roles. What initially sounded recondite is now a facile observation of fact. It is the examination of how this “previous acting experience” epiphany influences an audience’s viewing of the film that is the most useful and interesting part of the paragraph, not the tortuous stuff that introduces and surrounds it.

This brings me to my second claim, that excessive recourse to deconstructionism negatively impacts critical thought. For decades, scholarly writing has incorporated the concepts of différance, presence/absence, readerly/writerly texts etc., and also the hellaciously turgid, pleonastic, euphuistic, and sesquipedalian prose style excerpted above. The grand old men of deconstruction don’t get a free pass here, but they are exculpated to some extent by dint of the fact that they articulated the theories first. The thing is, though, that the axioms of Western philosophy and literature have been rigorously scrutinized since the sixties, and it therefore becomes harder to create fresh approaches. Often the critical game feels rigged so that the conclusion is established before the premises: i.e. ontology is dicey, intertextuality runs riot, meaning is not fixed, and relativism is all that can be established. Against this backdrop, it is difficult to construct a novel interpretative opinion.

Stam’s chapter does a reasonably good job of wielding the aforementioned deconstructionist tools, and his insights, when stripped of their verbiage, have merit. His conclusion, however, is somewhat predictable, and sneakily disingenuous. He writes:

By adopting the approaches to adaptation I have been suggesting, we in no way abandon our right or responsibilities to make judgments about the value of specific film adaptations. We can – and, in my view, we should – continue to function as critics; but our statements about films based on novels or other sources need to be less moralistic, less panicked [sic, really?], less implicated in unacknowledged hierarchies, more rooted in contextual and intertextual history. Above all, we need to be less concerned with inchoate notions of “fidelity” and to give more attention to dialogical responses – to readings, critiques, interpretations, and rewritings of prior material (77-78).

Given that Stam begins by deconstructing fidelity, and continues to do so in various guises throughout the chapter, it is redundant to write, in case we hadn’t already noticed, that strict adherence to fidelity is not a good idea. But the sneaky bit of his argument is his reassurance that ‘We can… continue to function as critics’; the subtext of this statement is that our critiques must incorporate the same deconstructionist techniques that he uses. The critic always interprets a film through her subjective lens, which is influenced by race, cultural background, sexuality, etc. etc., all of which can then be deconstructed again. The “dialogical” approach that Stam argues for risks being internalized by the critic and her inbuilt prejudices; and the result is worryingly solipsistic.

Nevertheless, deconstruction is not itself evil, or damaging; it’s just a theory, and much like evolutionary or atomic theory it is often unfairly judged on the supposedly bad things it has produced. Yet its current usage tends to reproduce the same tired tropes again and again. Historical, social, and cultural contexts do tend to affect audiences in similar ways, and therefore reasonably confident critical assertions can be made. Yes, ambiguity is always going to be present, but, as Ezra Pound commanded, make it new. Then again, he was a fascist, and they tend to have definite opinions.

Works Cited:

Stam, Robert. “Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation.” Film Adaptation. ed. and intro. by James Naremore. Rutgers UP, 2000. pp. 54-78.